Visiting the Red Clay Women of San Marcos Tlapazola, Mexico

Oaxaca is rich in tradition, craft, and Indigenous resilience, and nowhere is that clearer than in San Marcos Tlapazola, a Zapotec village known as the “red clay village.” With our guide Edmundo leading the way, we left the colourful colonial Oaxaca City centre and headed to the lush green foothills to visit the workshop of the Mujeres del Barro Rojo, or the Red Clay Women, a ceramics cooperative run by renowned artist Macrina Mateo Martinez.

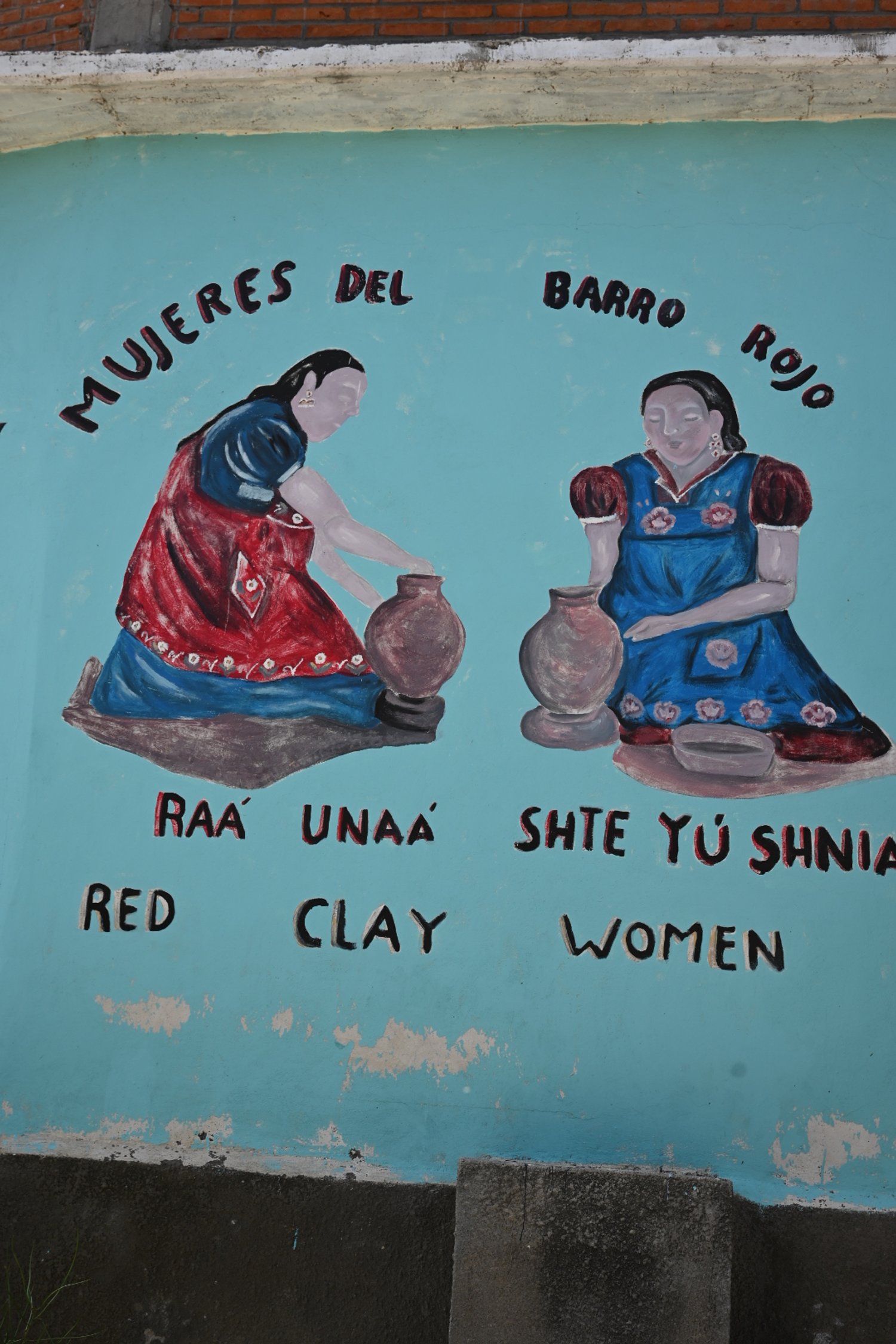

After a drive past many blue agave fields, we arrived at the studio, which has a vibrant mural of the sun encircled by red clay pots on the outside wall. The sign, written in Spanish, Zapotec, and English, reads: “Mujeres del Barro Rojo, Raa Unna Shte Yuu Shnia, Red Clay Women. We are the women who work the red clay of San Marcos Tlapazola.” We passed through a massive blue metal door, to enter a spacious courtyard painted bright fuchsia, where we met Macrina.

The Legacy of Red Clay

Macrina has been working with clay for over 40 years, having learned the craft from her mother at just seven years old.

Macrina welcomed us to her studio and showed us around her shop and gallery. She showed us photos to describe the process the women take to create their red clay pots. Through Edmundo, who acted as both tour guide and translator, Macrina told us they start right at the beginning, by collecting clay once a year from the mountains. It’s a labor-intensive process: the women hire a truck and pack a lot of bags to collect as much clay as they can carry. Once they return to the studio, the clay is dried in the courtyard, then sieved to remove debris, and rehydrated with care—a step familiar to anyone who has reclaimed their own clay. The pots are fired once in an open courtyard kiln, a method distinctly different from the bisque-and-glaze firing we use in our studio.

A Studio Without a Wheel

We really wanted to learn how the pots are made so Macrina gave us a demonstration. We asked her to demonstrate a bean pot, which is the traditional ware beans are cooked in. We learned that all her pots are actually made with yellow clay because it is easier to source. She started by wedging the clay and adding grog, or sand, to the clay. As she worked, she continued to sprinkle clay sand to prevent sticking, shaping a cone with her hands and using a corn cob to roll and refine the form.

Instead of an electric pottery wheel like Wedge’s ShimpoLites, Macrina uses a stool topped with a rock, a layer of clay sand, and the cheek of an old basketball. With this, she spins the pot by hand, using her left hand to turn the piece and her right hand to shape it. Her tools include many of the same tools we use at Wedge, as well as different tools like soft leather for smoothing and shaping, and a corn cob to refine the pot’s surface. The fluidity and precision of her movements were amazing and impressive to watch. The pot took Macrina less than 15 minutes to make! She told us that once the finished piece dries a bit, she will apply about five layers of the red wash, allowing each layer to dry in between, giving it the iconic red colour.

Clay as Empowerment

As she worked, Macrina shared stories of her life. Fifty years ago, Zapotec women were expected to remain housewives, but that didn’t sit right with her. Against the odds—and her mother’s concerns about societal judgment—Macrina started traveling to nearby villages to sell her pots. She faced criticism, but she persevered. In fact, many of her early critics now create and sell red clay pots themselves!

Macrina is acutely aware of the barriers she’s broken and the legacy she’s building. She spoke of the empowerment she’s found in working with clay and her pride in inspiring women across Mexico and beyond. She is grateful to clay for everything it has brought her, reflecting on how it’s not just a livelihood but a passion and a source of liberation. She’s traveled internationally, been featured in the New York Times, and continues to break boundaries, demonstrating that ceramics is a bridge between heritage and contemporary expression.

Her insights are profound. She told us that clay has memory, something we often discuss in ceramics, but she framed it differently: clay feels emotions. If you’re angry or sad, the clay resists; when you’re in harmony, the process flows. Anyone who works with clay can certainly resonate with this!

An Unforgettable Encounter

Visiting Macrina’s studio was more than just a lesson in pottery—it was a glimpse into a world where craft, culture, and Indigenous resilience intertwine. Her story is a testament to the power of clay as a tool for empowerment and change. We left San Marcos Tlapazola inspired, carrying with us not just new (to us) ways of working with clay but the deeper meaning behind her work: the courage to defy norms, the strength to pursue passion, and the wisdom to honor tradition.